“I am not a self-made man. You understand that you are here because of a lot of help then you also understand that now is time to help others.’” – Arnold Schwarzenegger

Martin Luther King, Jr. doesn’t need me to write about him. So, I won’t. I’ve actually written about him before here.

I’m writing to take my own advice. I’m not quoting the man. I’m taking his lessons and applying them to my own life. This post is about my deeper work and what I’ve learned. So, I start with a brief foray into pop culture.

The Sum of the Parts

The hit series Stranger Things just ended. I’m a fan of the show and found it to be all the positive things said about it.

Above all, it made me think, especially about the concept of the “hive mind.” It took me a while to figure out what that was, but after some research and thought, I believe I figured it out.

A “hive mind” is when a bunch of individuals act like they’re one shared brain.

- Each person (or insect, or Demogorgon) follows simple rules and pays attention to what others are doing.

- No single leader is in charge, but the group still seems coordinated.

- The “mind” is really the pattern of everyone’s choices adding up. It’s like a crowd forming lanes on a sidewalk, or bees “voting” on a new nest site by following and copying certain signals.

So, the hive mind is group behavior that looks like one intelligence, even though it’s made from lots of small, individual actions.

I find this to be a compelling metaphor for the way human lives are intertwined. When one sufferer sends out a tendril of pain or fear, it touches every other part of the whole. This isn’t just dramatic storytelling on the part of the Duffer Brothers (creators of Stranger Things) It’s a reflection of a truth recognized across human history…

What hurts one of us hurts all of us.

A Philosophical Web

Naturally, this reminded me of philosophy, which at its heart is teaching us how to be better versions of ourselves, not only for ourselves, but for others. The ancient Stoics taught that humans are not solitary atoms drifting in a void, but participants in a grand oikos, which is a common household of humanity. Marcus Aurelius wrote:

“What injures the hive injures the bee.”

This simple line captures a fundamental truth: Our wellbeing is collective, not individual. The Stoics saw virtue as something that flourishes in community, not isolation. When we harm one another, we harm ourselves.

Conversely, when we do good for another, we do good for ourselves.

Eastern philosophies make the same claim through different language. Buddhism speaks of pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination), which is the idea that everything arises in relation to everything else. There is no separate “I” untouched by the world’s suffering. Hindu thought teaches ātman (self) is brahman (universal), meaning the self is inseparable from the whole.

These traditions converge on one idea: you cannot exist in isolation from others.

Let me share another pop culture reference. In the season 3 episode of Bluey called Pass the Parcel, the kids play a party game called pass the parcel. In the game, the kids sit in a circle and pass a wrapped “parcel” around while music plays. When the music stops, whoever is holding it unwraps one layer, then the music starts again. The game ends when the last layer is unwrapped, usually revealing a prize. Lucky’s Dad insists on the “old-school” rule: only one prize in the very middle, not a present in every layer. Bingo, Bluey’s sister, keeps missing out and gets discouraged, but after a few parties the kids learn to handle losing better, and even start to enjoy the suspense of playing for the one big prize. Ultimately, this conversation stood out to me:

Chilli (Mum): “I’m sorry you didn’t win Pass the Parcel, Bingo.”

Bingo: “It’s okay, I don’t mind.”

Chilli: “Really?”

Bingo: “Yeah. When Lila is happy, I’m happy.”

Chilli: “Oh, Bingo.”

Bingo: “Maybe next time.”

What started initially as a “zero-sum game” turned into the realization that others winning does not mean I lose – or in this case, Bingo. Destroying the fallacy of zero-sum game ensures we all can flourish.

Science and Society Agree

Modern research echoes these ancient truths. Social scientists have shown repeatedly that policies and social structures that harm one group diminish life outcomes for the entire society.

Take the phenomenal work of The Sum of Us by Heather McGhee. McGhee describes how racism isn’t just a moral wound inflicted on Black Americans and other marginalized groups. It damages the economic and civic health of white communities too. For example:

- Cities and towns that accepted segregationist policies often ended up with poorer infrastructure, underfunded schools, and weaker economies—outcomes that hurt everyone, not just people of color.

- States with higher levels of racism tend to have worse public education, poorer healthcare outcomes, and lower life expectancy across racial groups.

McGhee writes:

“When we tax ourselves to segregate ourselves, we all end up poorer.”

This isn’t theory. Her entire work showcases evidence that the hive suffers when any part is denied equity and justice. Her work demonstrated and showed with evidence the tangible interconnection of communities throughout America have been damaged racism collectively. Yes, some flourish because of racism, but not many, and it’s almost always the same – rich whites with generational wealth.

We see this tangible interconnected damage in the following:

- Public Health: During COVID-19, we learned that viruses don’t check passports or incomes. When people are denied care, lack paid sick leave, or live in crowded housing, infection spreads more rapidly across populations. One person’s lack of protection became everyone’s vulnerability.

- Economics: When wages stagnate for the bottom half of income earners, aggregate demand falls. Businesses struggle. Economic growth slows. The wealthy do better than ever — but the whole economy weakens because so many people lack purchasing power. A rising tide doesn’t lift all boats when most boats are anchored.

- Climate: Pollution from wealthy nations drifts across borders. Wildfires, rising seas, extreme weather — none of these respect lines on a map. Damage to one ecosystem affects the global atmosphere.

McGhee argues that when white Americans buy into a zero-sum story—believing that if people of color gain, white people must lose—they often support policies that block shared public goods like strong schools, public pools, health coverage, and fair wages. The tragedy is that these choices don’t just harm the targeted “others;” they boomerang back and weaken the very systems everyone relies on, leaving working- and middle-class white communities with fewer resources, weaker services, and less opportunity. In McGhee’s framing, racism becomes a kind of “drained pool” politics: the effort to prevent someone else from benefiting ends up draining the pool for all the have-nots, including many whites.

What harms the hive, harms the bee.

Anger Rising

It would be easy to direct our frustration at everyday people: The neighbors who shrug, the coworkers who say one thing at work and another online, the well-meaning friends who talk about justice but vote for policies that entrench inequality.

But the real architects of these fractures are the powerful: The wealthy elites who control capital, media, and political influence. They profit from division. They know that a fractured populace is easier to manage than a unified one.

As labor organizer and socialist Rosa Luxemburg wrote:

“Freedom is always the freedom of those who think differently.”

But those in power don’t administer freedom equitably. They benefit when we are distracted by culture wars, tribal anger, and individual grievances. They want “compassion” in sound bites, but not in policy. They want us to feel like we’re doing something while the structures that concentrate wealth and power remain untouched.

And the weak-willed are not innocent. They do not get a pass.

To those who passively enable this system: your silence is a form of consent. Speaking out of one side of your mouth while supporting, enabling, or not challenging inequitable systems is not neutrality: It’s complicity at best and at worse condoning of the system that harms everyone not at the top.

If, as the Stoics believed, we are all part of a single organism — then apathy toward the suffering of others becomes apathy toward our own flourishing.

So What Do We Do? Widen Your Circle

I can only speak for myself; but as an American in today’s world, it’s incredibly difficult not to be emotional about the challenging condition of the United States, and how our instability, chaos, and rampant stupidity is having such negative reverberations across the world.

The “what do we do?” can’t just be outrage or withdrawal. It cannot be rage scrolling, which I admit I get caught up in way too often. Those reactions are understandable, but they shrink our world and harden our hearts.

A better path is to expand our circle of concern.

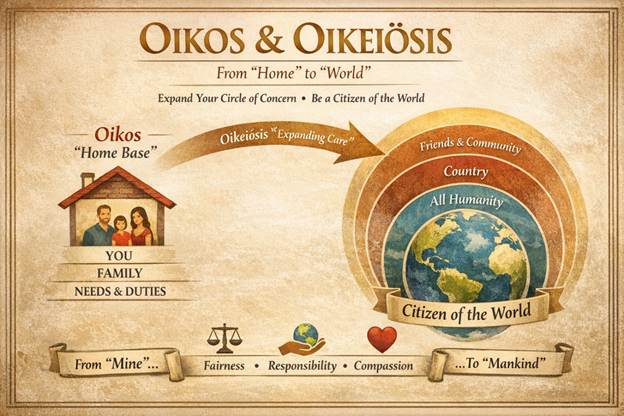

The idea of the “Circle of Concern” is associated with Hierocles, a Stoic philosopher who likely lived in the 2nd century CE. He described our obligations as a set of concentric circles—from self, to family, to community, to all humanity—and argued that ethical progress means pulling the outer circles inward, treating those farther away as more like kin.

Start close to home by tending to what we can control (our conduct, our words, our responsibilities), then widen outward through deliberate civic practice. We can do this by listening across difference, refusing zero-sum thinking, and investing in the common good even when cynicism feels easier. This looks like choosing curiosity over contempt, rebuilding trust in small places (workplaces, neighborhoods, schools), and aligning our time, vote, voice, and dollars with efforts that protect the vulnerable and strengthen shared institutions. We don’t heal a fractured society by winning arguments online; we heal it by practicing solidarity in real life over and over until “us” becomes large enough to include the people we’ve been trained to dismiss.

The Hive Is Real

Whether through the lens of philosophy, science, or lived experience, the message is clear: We are interconnected. Like the hive mind in Stranger Things, or the parcel game in Bluey, each pain and each win reverberates. Each wound weakens the whole. Each act of justice strengthens it.

And the greatest liberation we can pursue personally, socially, and/or politically is understanding what you do for others, you do for yourself.

© 2026 HR Philosopher. All rights reserved.